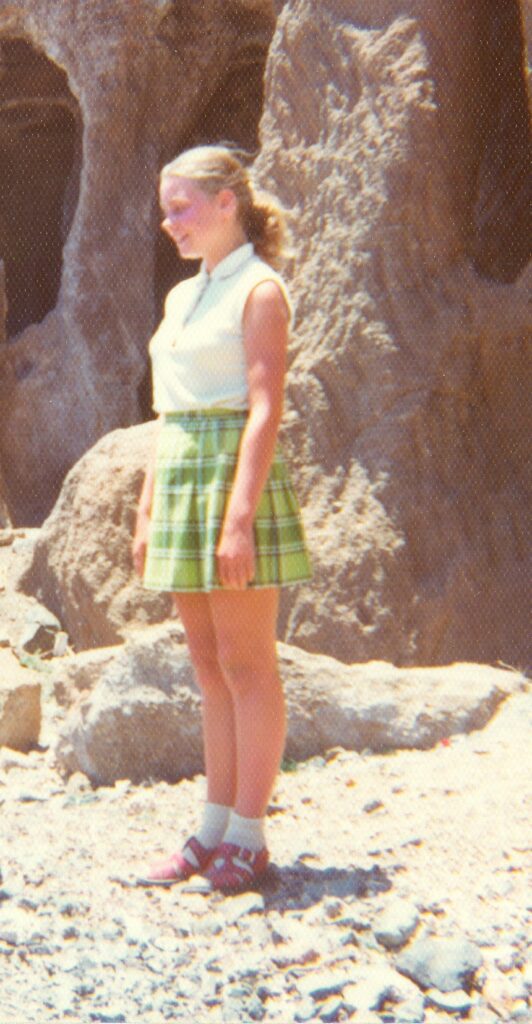

My house is being remodelled so I am cleaning up, deciding what can stay and what can go. I have come a long way, only the attic remains to be tackled. That will be a tough job, both physically and emotionally, because there are memories, sometimes almost forgotten, hidden in what is stored there. One Tuesday afternoon I set out to work, I clear out a crammed attic closet and take my time. I feel the grainy old paper of my elementary school diplomas, I unfold crumpled embroideries and find some clay work from the past. I sit down and browse through my photo albums. My young father and mother look happy. I see myself, a baby with fat cheeks and an open gaze. There are photographs of that baby in the stroller in the woods, playing in the playpen and lying on a rug in the garden. In a photo taken a few years later, I am a toddler, dancing around. My skirt swings up, I have my arms wide. A photo of a carefree childhood.

Gone

It is only because I know when that came to an abrupt end. There is nothing about it in those photo albums. What came later is visible again: high school, plenty of vacations, a boyfriend, a marriage, two children. I see myself posing and smiling. But my carefree life was over after the age of ten. I find the photo in which I am standing in front of the house with my bike in my hand, on my way to high school for the first time. I especially notice that bulging face, caused by the prednisone. I suddenly remember my 13-year-old self who still tried to participate in field hockey during gym class but who later couldn’t use her sore hands all afternoon. In photos from a few years later, I see how I deliberately keep my hands, already deformed by juvenile arthritis out of sight. A photograph only reveals much if you know what is behind the image.

The pain of my parents

Whole sections of my story are missing in those photo albums. I had to take four pills every six hours. Invariably my father would stand by my bed at midnight and at six in the morning to wake me up. Sleep-drunk, I would then take the glass of water from him and those pills that came with it. My mother drove me to school or to afternoon clubs when cycling was impossible because of inflammation. Every three months, I had to go to the paediatrician for a check-up. After every medical check-up my mother would invariably go to bed that night with a severe headache. Only when I was an adult did I realize how much grief my parents must have felt because of my arthritis. How much they did to help me in my struggle to build a nice life. And how happy they must have been when it all worked out for me: an education, friends and, above all, basically staying who I was, a curious person with an open mind.

Scrapbook

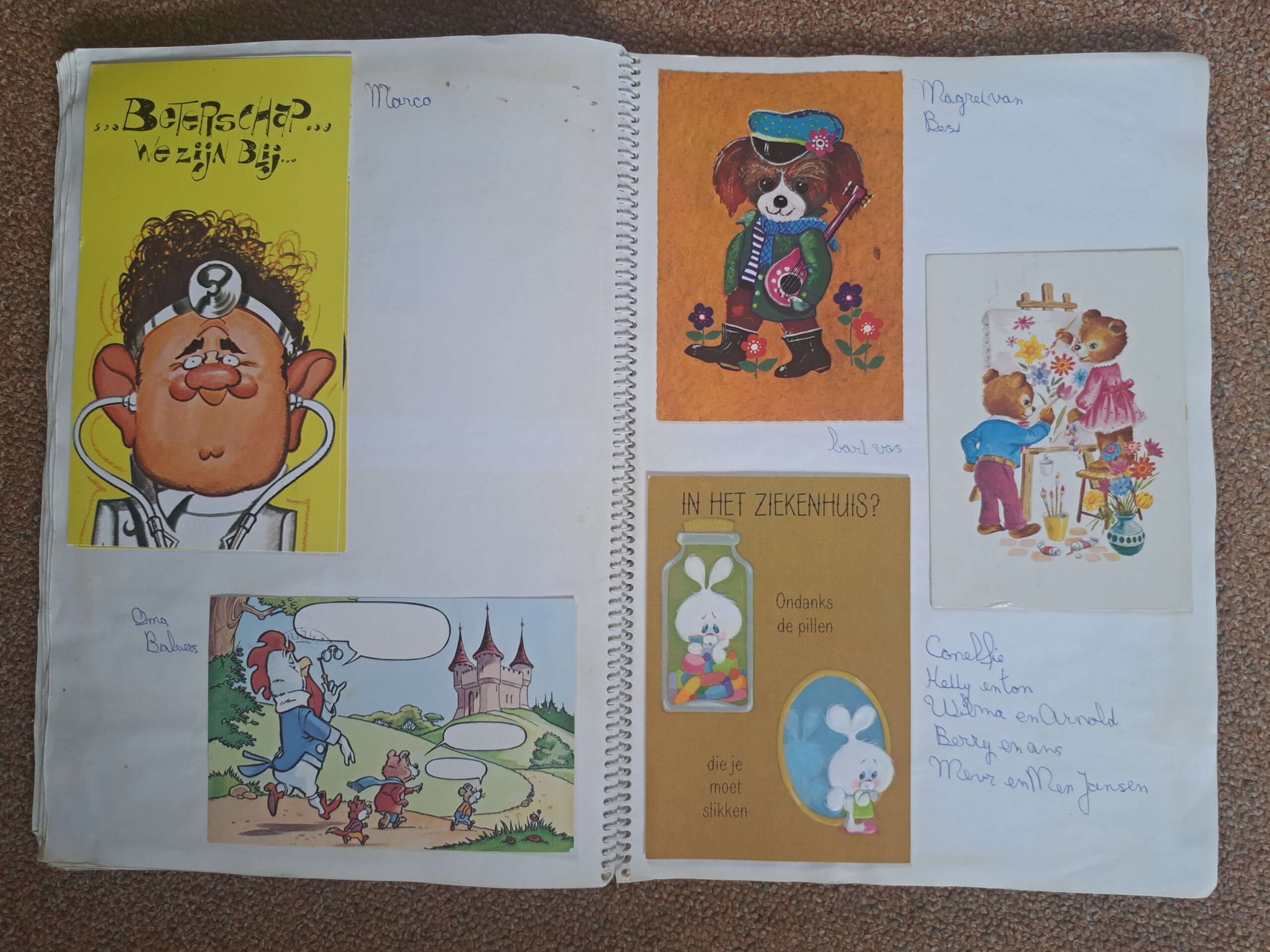

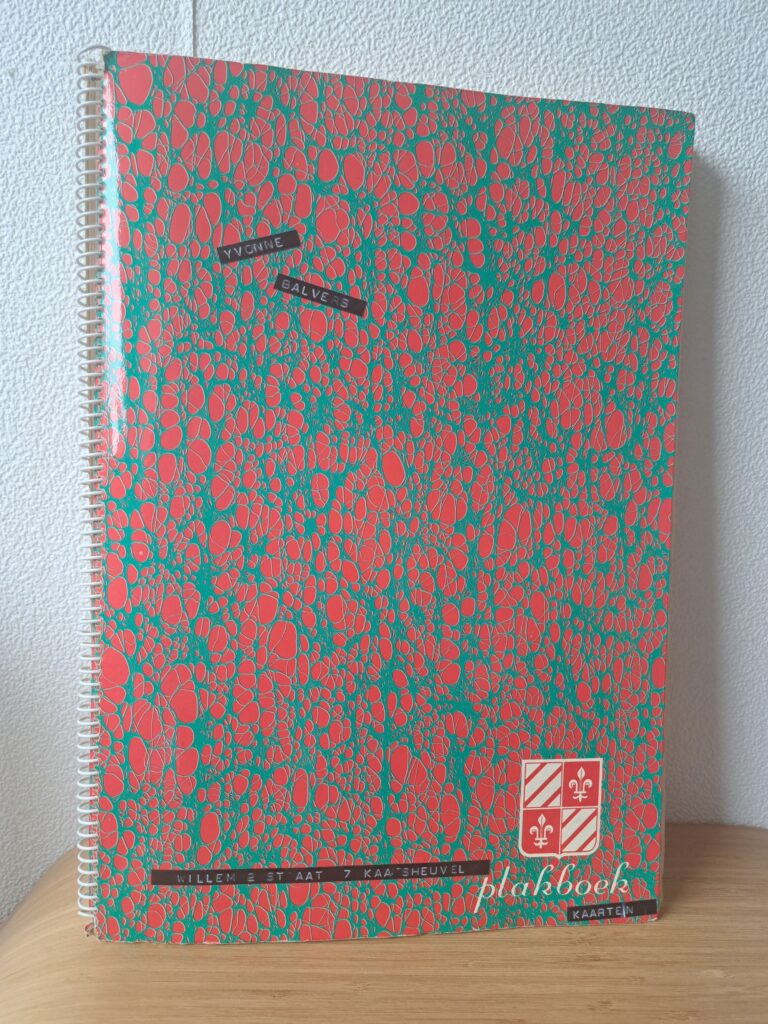

Among the photo albums, I find a thick scrapbook with a green-red cover. It doesn’t say anything to me at first. I open it up and the lump in my throat, already present because of the abundance of memories, grows. I let it happen and cry. I know this scrapbook very well. I have been in the hospital for three months, I am ten and have juvenile arthritis. All kinds of medication is tried on me but my body does not respond well. Children with various illnesses and diseases come and go, nurses appear and disappear. The getwell cards I get go into a scrapbook. I have many doubles, there are fold-out cards and cards with flowers and animals. I like the few textured postcards with a 3D effect the best where you can move the image back and forth in front of your eyes. I spend hours flipping through that scrapbook. All those colourful cards form a connection to the ordinary world outside the white hospital. Fifty years later, I am flipping through that scrapbook again, letting my emotions run free and moving my fingers over the paper. I read the names of senders sometimes long-forgotten. A large yellow envelope that contained an inflatable giraffe has come loose and I feel the grains of dried-up glue-stick. The letters that classmates(at the teacher’s request) wrote to me sit together in a glued brown envelope. The last card is from the neighbours, with “welcome home” handwritten on it. It sits lonely in the left corner of an otherwise blank page. After that three more blankpages remain. I close the scrapbook and become aware of my warm cheeks and wet red eyes.

Child with juvenile arthritis

Once back home from that hospital, I felt strange, different. I wasn’t just another kid, but that kid with juvenile arthritis who sometimes couldn’t participate. New friendships had been made at my school and in my neighbourhood without me, and old friendships felt uncomfortable. After my tenth year, walking became difficult, pain was a daily presence. In time, I could no longer run, no longer jump, no longer dance. Back then I didn’t have the words to understand what all that does to you, let alone explain it. But now I can tell about loneliness and sadness, about how you keep running into your own limitations while peers around you don’t even notice. I can now explain why I doubted saying “I can’t do this”. Why I sometimes hesitated to go anywhere. My life with juvenile arthritis became demanding, required constant planning, thinking ahead and taking pros and cons in consideration. Do I participate, can I hang in there, how much pain and fatigue will it cause me? Do I make myself the exception, the one on the sidelines, the one who stands out, who is different? Or do I stay at home where I don’t have to explain anything? Over and over again you have to take into account your limited energy, when to take those pills, whether or not you are overstepping your limits. And sometimes you consciously choose to do that, knowing that it will cost you days of recovery.

A full box

I clean out the attic. Of that full closet, only one box of mostly paper memories remains. With care I add the scrapbook, which I keep intact. It is a tribute to myself and the tangible evidence of a period that has had a great influence on the rest of my life. I have become an older woman whose life choices were determined in part by my juvenile arthritis. Sometimes I stand on that sideline, sometimes I stand outbecause I am and act differently, but I don’t care about that now. I have gotten to know my limitations and found ways around them, without worrying about what others might think. There is so much I can do and I consider myself a lucky person. But the lost child with juvenile arthritis is still deep inside me. Brave child, comehere, I embrace you.

This essay was the winner of the 2025 STENE PRIZE

Back to english stories

ScrapbookAmong the photo albums, I find a thick scrapbook with a green-red cover. It doesn’tsay anything to me at first. I open it up and the lump in my throat, already presentbecause of the abundance of memories, grows. I let it happen and cry. I know thisscrapbook very well.I have been in the hospital for three months, I am ten and have juvenile arthritis. Allkinds of medication is tried on me but my body does not respond well. Children withvarious illnesses and diseases come and go, nurses appear and disappear. The getwell cards I get go into a scrapbook. I have many doubles, there are fold-out cards andcards with flowers and animals. I like the few textured postcards with a 3D effect thebest where you can move the image back and forth in front of your eyes. I spendhours flipping through that scrapbook. All those colourful cards form a connection tothe ordinary world outside the white hospital.Fifty years later, I am flipping through that scrapbook again, letting my emotions runfree and moving my fingers over the paper. I read the names of senders sometimeslong-forgotten. A large yellow envelope that contained an inflatable giraffe hascome loose and I feel the grains of dried-up glue-stick. The letters that classmates(at the teacher’s request) wrote to me sit together in a glued brown envelope. Thelast card is from the neighbours, with “welcome home” handwritten on it. It sitslonely in the left corner of an otherwise blank page. After that three more blankpages remain. I close the scrapbook and become aware of my warm cheeks andwet red eyes.Child with juvenile arthritisOnce back home from that hospital, I felt strange, different. I wasn’t just another kid,but that kid with juvenile arthritis who sometimes couldn’t participate. Newfriendships had been made at my school and in my neighbourhood without me, andold friendships felt uncomfortable. After my tenth year, walking became difficult,pain was a daily presence. In time, I could no longer run, no longer jump, no longerdance. Back then I didn’t have the words to understand what all that does to you, letalone explain it. But now I can tell about loneliness and sadness, about how youkeep running into your own limitations while peers around you don’t even notice. Ican now explain why I doubted saying “I can’t do this.”. Why I sometimes hesitatedto go anywhere. My life with juvenile arthritis became demanding, required constantplanning, thinking ahead and taking pros and cons in consideration. Do I participate,can I hang in there, how much pain and fatigue will it cause me? Do I make myselfthe exception, the one on the sidelines, the one who stands out, who is different? Or2025 STENE PRIZE

do I stay at home where I don’t have to explain anything? Over and over again youhave to take into account your limited energy, when to take those pills, whether ornot you are overstepping your limits. And sometimes you consciously choose to dothat, knowing that it will cost you days of recovery.A full boxI clean out the attic. Of that full closet, only one box of mostly paper memoriesremains. With care I add the scrapbook, which I keep intact. It is a tribute to myselfand the tangible evidence of a period that has had a great influence on the rest ofmy life. I have become an older woman whose life choices were determined in partby my juvenile arthritis. Sometimes I stand on that sideline, sometimes I stand outbecause I am and act differently, but I don’t care about that now. I have gotten toknow my limitations and found ways around them, without worrying about whatothers might think. There is so much I can do and I consider myself a lucky person.But the lost child with juvenile arthritis is still deep inside me. Brave child, comehere, I embrace you.Author: Yvonne Balvers2025 STENE PRIZE